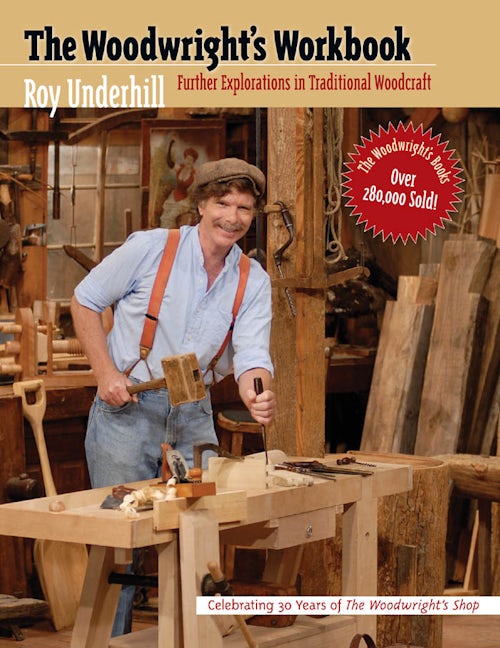

The Woodwright's Workbook

Further Explorations in Traditional Woodcraft

By Roy Underhill

256 pp., 8.5 x 11

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-4157-0

Published: November 1986 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-6979-6

Published: November 1986 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-6726-1

Published: November 1986

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2008 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

Saying "No!" to Power Tools: A Conversation with Roy Underhill.

Q: How does The Woodwright's Guide differ from other books in the Woodwright's series?

A: The Woodwright's Guide is an environmentally organized guide to woodcraft. It starts in the forest with felling the tree and ends with the final finishing in the workshop. My other books have followed a similar path, but this is the most comprehensive guide in the series, benefiting from thirty years of experience. It is also my first line-illustrated book with brilliant drawings by my daughter Eleanor. Her drawings, done from my photographs, give clarity to the ideas but retain the specificity of the places and the real people who do this wonderful work.

Q: How did your collaboration with your daughter, Eleanor come about?

A: Both my daughters, Eleanor and Rachel, worked with me on television and traveled with me to museums around the world. When it came time for the new book, I was looking at thirty years of photography of tools and techniques. Having Eleanor make drawings from the photos gave us both consistency and specificity.

Actually both daughters worked on the book. Eleanor did the drawings, and the ones that needed retouching went to Rachel. Both my daughters grew up surrounded by wood and tools, and it's wonderful that we can still work together!

Q: Are there any special features of this book you'd like readers to be aware of?

A: The Woodwright's Guide is a book with grain--just like wood. You can work it with your left-brain intellect, following the ideas in the text like a wedge following a split. You can also engage your right brain by grasping the "gestalt" captured in the illustrations. You can also put both the brain and hands to work because in the back of the book I have plans for workbenches, screw-cutting engines, and treadle lathes. I only regret that we weren't able to include a few Band-Aids with each copy--but that's in the works.

Q: What is the meaning of the book's subtitle, Working Wood with Wedge and Edge?

A: The thread of "wedge and edge" runs through the entire book. A blade meeting wood either splits it as a wedge or cuts it as an edge. Wedge and edge consciousness in your woodworking gives meaning to the feedback through the tool handle, guiding your decisions with every move.

Wedge and edge means honest woodworking that engages both the grain and the brain.

Q: What do you hope this book will impart to your many readers and fans?

A: I hope everyone can share the sense of wonder at the complexity and beauty of our connection to tools and wood. Our language, our culture, our ways of thinking, all evolved with the tools in our ancestors' hands. Artisanship in wood is part of every human's legacy, so let's honor it.

And it's not just nostalgia. We know that biodiversity is important to us. Well, so is techno-diversity. We can value heirloom technology just as we value heirloom tomatoes. It may not be commercial, but it sure tastes better!

Q: What led you to give up power tools and devote yourself to a career of working exclusively with hand tools?

A: During the back to the land movement of the 1970s I was homesteading in the New Mexico mountains, struggling to live off the grid. A chance encounter with a tool collector's trove of treadle-powered tools made me realize that an advanced technology of non-electric machines had once flourished and then been abandoned. This was during the energy crisis of the 1970s and the deep significance of sustainable technology hit many of us like a trip hammer (a water-powered trip hammer, of course).

Q: What about woodworkers who blend the use of power tools with hand tools? Is this book also for them?

A: Curiosity is the ultimate power tool. If you work with wood, or just live on a planet where people work with wood, this is the book for you. That's because The Woodwright's Guide cuts deep, both into the way wood works, and into the history of the way we work it. So, if you're trying to do better at a single task of joinery, this book brings you the observations of a thousand years. And, if you're curious about our enduring relationship with the natural world, The Woodwright's Guide will give you a sharper axe to hew your own insights.

Q: What have you been up to since your last Woodwright's book, published in 1996, and how has it influenced this volume?

A: Shooting the PBS series The Woodwright's Shop gives me the chance to travel and meet craftsmen and women from all over the world. It's astounding the extraordinary depth of knowledge so many people have about specific areas of the craft. But it's the stories I appreciate the most. From woodcarver Nora Hall, I heard stories of her father's carving shop during the Nazi occupation of Holland. Even the work-worn log cabins and ground-down tools preserved at the Museum of Appalachia tell stories--stories of life and hard work in America's "wooden age."

Q: What or who have been the major inspirations during your career?

A: Working at Colonial Williamsburg (in spite of the fife and drum parades) was my university of hand craft. The master craftsmen at Colonial Williamsburg are people at the top of their art. It was a constant struggle for me to live up to their high standards of historical research, craftsmanship, and aesthetic sensibility. Still, it was a great place for me, a generalist, to be. If I needed to know something about wheel wrighting, blacksmithing, cooperage, or any of the trades that built our civilization, all I had to do was walk down the street and ask one of the master craftsmen. As Francis Bacon put it, this was a place where "Many ingenious practizes in all trades . . . shall fall under the consideration of one man's mind."

Q: You wrote your first Woodwright's Book in 1981, over 25 years ago. Have you seen a resurgence in interest in hand-crafted woodworking during this period? Have attitudes changed? Has working with hand-tools gone in and out of style, according to larger trends in popular culture?

A: The cycle of high tech and high touch goes back hundreds of years. The first hand-craft, how-to book in English, Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handiworks, was published in 1678. Even then, they were as much concerned with the virtues of "vanishing" hand craft as they were in getting the job done.

Now, of course, we are at a technical crossroads, and it's good to have a back-up in case the big machine breaks down or runs out of gas. And if you're going to have a hobby, it might as well be ethical. It seems counterproductive to make a nice wooden cradle for your grandchildren if you choose to make the planet uninhabitable in the process.

But even without the green issue, making things directly with our hands goes to the full depth of our humanity. We'll never be done with it. Making something gives us the same kind of primal happiness we feel when we encounter a berry bush loaded with ripe fruit. Just as the old hunter-gatherer still resides in each of us, so too does the ancient hand craftsman.

Q: How does the work you do and the way you do it connect to a larger philosophy of life?

A: It's a mission. With the gross failure of the intellectual class, it has fallen to the craftsman to expose the hidden power inequities of society. Subversive woodworking has to take the lead, helping people make a choice between mindless consumerism and conscious craftsmanship. Just say "NO" to power tools! Let's take a bite outta Norm!

Q: Why do you think your many fans have coined the nickname "St. Roy" to describe their devotion to you?

A: I've cut myself so many times on the television program that I remind folks of unfortunate martyrs like St. Sebastian. He met his fate on the receiving end of arrows, and St. Simon has an even more distressing history with the saw. I have the chisel.

In my own defense, however, my TV director kept yelling "Cut!" and I was just trying to oblige.