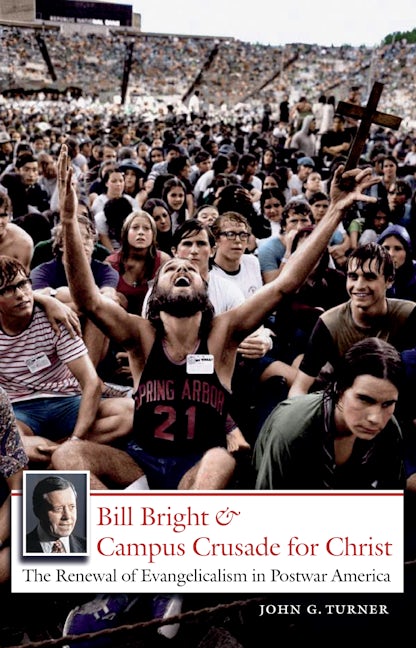

Bill Bright and Campus Crusade for Christ

The Renewal of Evangelicalism in Postwar America

By John G. Turner

304 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 20 illus., notes, bibl., index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-5873-8

Published: March 2008 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8159-5

Published: March 2008 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-8910-7

Published: March 2008

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2007 by the University of North Carolina Press. All rightsreserved.John G. Turner, author of

Q: How did you get interested in Bill Bright and Campus Crusade for Christ?

A: : I grew up in the world of parachurch evangelicalism. As a teenager, I belonged to Young Life, the most prominent evangelical ministry to high school students in the United States. At Middlebury College, I participated in InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, the second - largest American evangelical campus ministry. I knew about Campus Crusade because the organization had done much to shape my sister's spirituality at Cornell University. I once attended several Crusade events - including a pro-life movie that left quite an impression - during a weekend visit to Cornell. My sister even met her husband on a Campus Crusade mission trip to Estonia. This small amount of personal contact sparked my interest in the organization.

I wanted to write about post-WWII American evangelicalism from a previously unexplored angle and considered focusing on Young Life or InterVarsity. I quickly realized, however, that Campus Crusade would lend itself to a much more compelling narrative. The organization is much larger, raises considerably more money, and has been more controversial, primarily because of its more aggressive attempts at evangelism. The history of Campus Crusade tells us much about modern evangelicalism's relationship to the university, political conservatism, and issues of gender and sexuality. Also, Campus Crusade's founder, Bill Bright, was one of the five most influential evangelicals in the post-WWII United States. Yet despite the significance of Bright and his organization, historians have not paid much attention to Campus Crusade for Christ.

Q: What exactly is a parachurch? How significant a role do parachurch organizations play in American evangelism today?

A: Parachurch (from the Greek para or alongside) organizations exist outside the structures of denominations. They are "free agents," and the parachurch world suggests the free market nature of American evangelicalism. Evangelicals form parachurch organizations for many purposes: political advocacy, humanitarian efforts, and - for evangelicals, above all - evangelism.

Parachurch organizations have fueled the resurgence of evangelicalism in the United States since 1945. Ranging from the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association to World Vision to Campus Crusade for Christ, these organizations raise billions of dollars and exert a national influence on the very loose and disjointed evangelical movement. Unlike denominations, they typically have smaller layers of bureaucracy and respond more adroitly to changes in popular culture. Campus Crusade is one of the most significant parachurch organizations in the country today. No other parachurch organization raises as much money for the cause of evangelism.

Q: When and how did Campus Crusade for Christ begin?

A: Bill Bright founded Campus Crusade in 1951 and began his work at the University of California, Los Angeles. Prior to this step, Bright had bounced between several different attempts in business and at seminary education.

Bright's approach was simple but ingenious. A former student body president and fraternity member, he gathered a team of evangelists and visited Greek Row at UCLA. He also made appointments with star athletes on the campus, including several from UCLA's 1954 national championship football team.Campus Crusade self-consciously overcame the rather dour reputation of American fundamentalism - its staff members were young adults who still dressed and talked like collegians. They didn't waste their time critiquing fraternity parties but instead won converts by talking to people about a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

Q: Although this is an unauthorized portrait of Bill Bright and Campus Crusade, many current and former Campus Crusade staff members agreed to be interviewed for it. How do you think they will respond to your profile of Bright and their organization?

A: It's been a complicated relationship. I interviewed many Campus Crusade staff members, a few of whom later refused me permission to include their quotes in the book after reading a draft of the manuscript. Some were deeply offended by my use of the language of religious marketing to interpret Campus Crusade's activities and by my examination of Bill Bright's contributions to the politicization of evangelicalism. Evangelicals on the one hand and the worlds of academia and journalism on the other have a relationship marred by mutual suspicion and hostility. Also, I think the fact that Bill Bright died shortly after I began this project made these relationships more difficult. Several discussions were quite uncomfortable, but I remain grateful for the access I was given and for the dialogue with several critics.

At the same time, several other current and former staff members thought I portrayed Bill Bright very accurately and loved the book. I would be very grateful if other members and supporters of the organization read and responded to my history of their organization.

Q: How large is Campus Crusade today? Is it still growing? How would you characterize its current leadership?

A: Campus Crusade continues to grow, at least by some measures, and it has become much more than a ministry to college students. Campus Crusade staff members have evangelized remote corners of the world by translating the organization's Jesus film into more than a thousand languages andshowing it in rural villages. The organization's FamilyLife ministry invites couples to marriage workshops. Josh McDowell has organized humanitarian missions to the former Soviet Union. On the campus, I think Crusade is a bit less visible than it was back in the late 1960s, but that's partly because there are a multitude of evangelical campus ministries competing for attention today. Still, there are roughly 3,500 staff members working for Campus Crusade at American colleges and universities, and the organization has tens of thousands of additional workers and volunteers in its other ministries in the United States and internationally. The organization does not document large numbers of "decisions for Christ" in the United States but reports millions of such decisions each year around the world.

Even before Bill Bright died in 2003, Steve Douglass - a Harvard M.B.A. and longtime Crusade staff member - had assumed the organization's presidency. Douglass told me that his goal is to "get as many people into heaven as possible," and I think he will pursue this goal by streamlining the organization's ministries and sharpening their evangelistic focus. Also, I think Douglass will be a more circumspect leader than Bright - he intends to steer clear of political causes, for instance. Financially, Crusade is raising money at a rapid clip, having recently surged past the $500 million mark in annual revenue. It is unusual for a parachurch organization to thrive beyond the lifetime and presidency of a charismatic founder, so what Douglass has accomplished is quite remarkable.

Q: Why do you frequently use the words "marketing" and "selling" when describing Crusade's activities?

A: Such language infused Campus Crusade's early ministry. Bill Bright was a businessman. He asked his early staff members to read a self-help manual for salesmen, and he talked about evangelism as "Christian salesmanship." Bright even developed his famous Have You Heard of the Four Spiritual Laws? on the recommendation of a salesman. In the late 1960s, when Campus Crusade outgrew its early management structures, Bright recruited two Harvard M.B.A.s to make his operations more efficient. It is no accident that Bill Bright became one of the most effective evangelical fundraisers in the United States. He was without parallel at befriending evangelical businessmen and persuading them to dedicate their wealth to the cause of evangelism.

Q: What kinds of roles are open to women in Campus Crusade for Christ?

A: Campus Crusade does not have a formal policy on this issue - it's too controversial and divisive in the evangelical subculture today. Virtually all of Campus Crusade's top leaders are men, though I noticed that the organization recently added a second woman to its board of directors. In general, men serve as the directors of each of the ministry's campus chapters, but there are occasional exceptions. What's interesting to me is the distance that the organization has traveled on these issues since the 1950s. Despite popular perceptions, evangelical women have always provided significant leadership, sometimes in unacknowledged capacities. Even when organizational literature referred to them as "staff girls," female staff members were indispensable to the organization's efforts. When mainstream culture moved in a more egalitarian direction in the late 1960s and 1970s, evangelicals - Campus Crusade included - reacted by defending "traditional" gender roles and female domesticity. Campus Crusade's FamilyLife ministry, for example, believes that the Bible mandates male headship within the family. Despite such rhetoric, however, many evangelicals have stopped swimming so fiercely against the cultural tide on these issues. Campus Crusade visibly promotes female leaders at its conferences and in its publications.

Q: How important were Bill Bright and Campus Crusade in the emergence of the Religious Right? Is the organization involved in politics today?

A: Bright played quiet but significant roles in the politicization of evangelicalism. Evangelicals were interested and occasionally involved in conservative politics long before the Moral Majority and Christian Coalition. In the 1950s, Crusade's fundraising literature and publications were imbued with a strong dose of anticommunism, and Bright endorsed an early effort to get Christians involved in precinct-level politics in the early 1960s. He attracted criticism from the media - and from some members of his staff - for a second such effort in the mid-1970s. He also built some of the interpersonal bridges between Republican politicians and evangelical leaders, and Bright helped articulate evangelical opposition to abortion and gay marriage.

Campus Crusade, however, is not and never was a political organization. Sometimes the organization undertook forms of activism that appeared political, as when Crusade staff and students counterprotested at SDS rallies in the late sixties and early seventies. But those were primarily attempts to attract attention and the opportunity to evangelize. Other staff members besides Bright have wanted to impact the direction of American politics. Dennis Rainey, president of Crusade's FamilyLife division, spoke out strongly against gay marriage after it was legalized in Massachusetts. Most staff members, however, concentrate on the organization's mission of evangelism.

Q: How would you characterize Bill Bright? What do you admire most about him? And least?

A: First of all, I did not have the opportunity to meet Bill Bright, so I know him through interviews with his family, supporters, and critics and through his writings and some correspondence. There are a few things that bother me about Bright. He persistently claimed that he had "never been involved in politics" when it was quite clear to me that he had been, at least on some level. Most of his other weaknesses, however, were quite ordinary. He could drive his staff to exhaustion, he bristled when criticized, and I think he had a salesman's tendency to overstate his accomplishments and those of his organization.

Still, on the whole, Bright was a very admirable representative of American evangelicalism. As an evangelist, he was the genuine article - even after he became busy and famous, he lived out his insistence that Christians continually talk to others about Jesus. He was a consummate fundraiser, but he avoided both the histrionics and scandal that have plagued quite a few evangelicals in this arena. He lived quite modestly, again particularly compared to many other prominent evangelicals. Bright wasn't an Elmer Gantry. Partly because of Jim Bakker, Jimmy Swaggart, and Ted Haggard, evangelicals have taken a beating for only hypocritically supporting "family values" in recent decades. I never heard a single whisper of sexual impropriety about Bill Bright.

Authors usually think their subjects haven't received enough attention, but outside of Billy Graham, it's hard for me to think of another post-WWII evangelical leader with a legacy larger than that of Bill Bright. Bright's famous tract - Have You Heard of the Four Spiritual Laws? - shaped the faith and evangelism of countless evangelicals, his organization helped fuel a resurgence of evangelicalism on supposedly secularizing campuses, and he channeled billions of American evangelical dollars toward the cause of global evangelism.