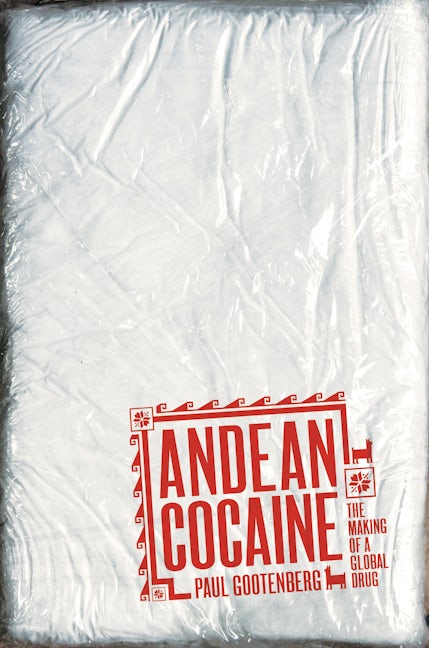

Andean Cocaine

The Making of a Global Drug

By Paul Gootenberg

464 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 16 illus., 4 figs., 12 tables, 2 maps, appends., notes, bibl., index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-5905-6

Published: December 2008 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8380-3

Published: December 2008 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-8779-0

Published: December 2008

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright (c) 2009 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

Paul Gootenberg, author of Andean Cocaine: The Making of a Global Drug, considers our long history with the demonized leaf.

Q: Why cocaine? Why did you choose to write about this drug?

A: Well surely not from great personal experience with the drug: I was a hardworking, sober, and impoverished grad student during the peak years of the U.S. cocaine boom in the early 1980s. However, I was also becoming at the time a kind of specialist on Andean export "commodities." My first two books, at least indirectly, dealt with 19th-century guano, a coveted fertilizer export to Europe found on islands of dried bird dung lying off the coast of Peru. Now, guano is a far more exotic good than cocaine, yet, in its time, it also integrated a faltering Andean nation into the world economy. When an old friend, a journalist reporting on drugs in the Andes, suggested to me in the early 1990s that little had been done on the history of cocaine, I got very curious. As I realized the number of interesting fields I'd learn about investigating such a history -- medical and cultural history, economic botany and sociology of the illicit, and so on -- I got hooked.

Q: Why is cocaine's history so dramatic and significant?

A: It's dramatic because cocaine, in a relatively short time, illustrates the phases that virtually all illicit drugs have passed through: first embraced as a miracle drug and promising commodity, then shunned by medical opinion, and finally transformed from the impact of legal prohibition into an illicit good. Cocaine's illicit rebirth was particularly dramatic after 1950 because it had barely registered before as a menacing drug.

It is also emblematically South American: although cocaine has been produced in other parts of the world (as the book shows, in Java and Formosa in the early 20th century), cocaine has been a predominantly South American phenomenon. Its raw material, coca leaf, is culturally indigenous to Andean peoples. Many of cocaine's innovations -- commercial and later criminal -- arose there, and the trafficking boom since the early 1970s has been one of Latin America's most lucrative and homegrown trades. Foreigners do not control it. These Andean historical roots are one big reason why the trade has been so difficult to stamp out.

Q: What role did the U.S. play in the rise of cocaine as a global phenomenon? How has this affected Latin America, where the drug is grown?

A: One of my key arguments is that a long politicized "commodity-chain" between the United States and the eastern Andes has been central to the drug's transformations since the 19th century. Of course, it also demonstrates a range of other vital historical actors along the way: modern German pharmaceuticals, French coca enthusiasts, Dutch and Japanese colonial enterprises, Bolivian coca nationalists, Cuban and Chilean smuggler diasporas, and others. And the United States has never been able to easily impose its will on the Andean actors in cocaine's history. However, by the 20th century, if one includes the leaf extract found in our national drink, Coca-Cola, the United States was the largest legal market. The Andes fell increasingly within an informal realm of U.S. political sway. And, by 1915, the United States began a lonely crusade to ban cocaine globally, which gathered few allies until after WWII. When cocaine reinvented itself as an illicit drug, in large part as an unintended effect of the 1940s-1960s U.S. campaign against it, Americans again became avid consumers. The ongoing "war" against Andean cocaine since 1980 has been inspired and run from Washington as well. So, cocaine has a special relationship with our own history.

As far as the Andes, it's a longer story. The book situates the rise of cocaine in new ways within Peruvian history, but since 1950, cocaine has also deeply affected Bolivia, and since 1970, obviously Colombia. The eastern Andes as a whole, its people, politics, and development, have been touched more by cocaine than by any other modern commodity. And the political conflicts with the United States still burn on at great human cost. Those latter cocaine histories (of Bolivia and Colombia) are sketched out in my book, but still need deeper research by other historians.

Q: Why is this book controversial?

A: No doubt my most controversial point is that the U.S. interventions in the Andes -- first, the pressures to proscribe legal cocaine and then coca after 1945, and then escalating covert anti-cocaine police actions throughout the 1950s and 1960s -- likely led to cocaine's expansion and then explosion by the 1970s. The actual turning point was Richard M. Nixon's repressive anti-drug regime, which in effect ushered in the hedonistic era of Studio 54. We might have done better had we just left Andean cocaine and coca leaf alone.

I think secondly, readers will be surprised by my discovery that Cold War politics also had a great deal to do with how illicit coke spread after 1945. For example, the impact of the 1959 Cuban Revolution was to exile and scatter early cocaine traffickers and its incipient use across the hemisphere. The U.S.-supported coup against leftist Chilean president Salvador Allende in 1973 drove the drug's exporting center to Colombia -- a country with little prior involvement with cocaine. Cocaine was an eminently "Cold War" product. Others will find some historical vindication here for the oppositional drug politics, say, of the current Evo Morales government in Bolivia. The country has a long but unknown history of defending national coca leaf against foreigners, yet Bolivians have carefully distinguished the leaf from the drug cocaine.

Q: How is your book different from other books about illicit drugs?

A: Andean Cocaine is unique in several ways. First, it is the first truly archival-based work on cocaine, or for that matter, any particular drug in Latin America, so there are many new and surprising findings. Secondly, its long time-frame (more than a century, from 1850-1980) makes it one of the only books on drugs to trace their initial creation, reception, and then decline and rebirth as a criminal good. The originality lies in how it details the actual emergence of an illicit drug on the ground. The book may also serve as a model for other scholars looking at drugs, in how it combines a local perspective (the eastern Andes) with an eminently global one, and how it combines the study of economic, social, political, and cultural currents in the making of modern drugs. It is a contribution to the "new" drug history.

Q: Who should read this book? What will they get out of it?

A: Everyone. OK, not exactly everyone. There is a broad fascination with drug cultures in the United States, where cocaine touched so many lives during the 1970s and 1980s, and I hope these general readers will be attracted to my work. Anyone -- political scientists, activists, or policy reformers -- seeking the roots of our current "war on drugs" in Latin America will surely profit from the book, as will many students of history (Latin American, trade and commodities, world, and so on), or anthropology students drawn to Andean culture or cultures of consumption.

I think readers will not only get a newly de-centered view of drug trades, anchored in the Andes, but also a more holistic picture. Andean Cocaine is a remarkable story, one that reveals, like other new commodity histories, the unexpected connections that formed the modern world. I like to think of it as a hidden and underground chapter in the history of globalization.

Q: Is there anything that will shock readers?

A: I bet UNC Press readers are not easily shocked. However, some may not realize the extent to which coca and cocaine have played a long part in American culture -- the book details, for example, Coca-Cola's century-long hidden interests in the Andean leaf. They also may not realize cocaine's contribution to post-war culture (Mambo, Bebop, and disco, if the latter is really culture). Others might be surprised to learn about the dynamic roles that women played as early drug traffickers -- for example, the flamboyant Bolivian Blanca Ibanez de Sanchez was a pioneer, smuggling cocaine across the hemisphere during the late 1950s. Some readers will raise an eyebrow about my insistence on the "agency" (as academics call it) of local Andean actors, such as Lima cocaine scientist Alfredo Bignon or cocaine magnate Andres Soberon. They were a major force in the formation of cocaine. But most of all, I hope that they are shocked and pleased to discover that the history of drugs can be "serious," deep, and engaging history, not just sensationalism or opinion.

Q: What is the status of cocaine in the world today? What is the U.S. doing about it?

A: Cocaine use peaked in the United States during the early 1990s, but we remain the world's leading consumer of the drug. There is less hysteria about cocaine than that which currently surrounds "meth," but millions still use cocaine, albeit in a more normalized way than during the cocaine heyday of the 1980s. It seems to be a "whiter" drug again, less associated with "crack." Meanwhile, the forceful interdiction policies of the DEA in the Andes now concentrate on Colombia, where coca and cocaine became an integrated industry after being largely pushed from eastern Peru and Bolivia during the late 1990s. This policy has only helped to spread the drug globally. Today, usage continues to grow in Europe and the former Soviet Union, and surprisingly, Brazil has emerged as the second most consuming nation.

The cocaine trade garners nearly $50 billion yearly, in risk-inflated revenues, and remains a very lucrative trade. The DEA claimed some "success" with cocaine eradication in Colombia -- in 2007 the price of the drug rose for the first time in their 30-year war against it. However, the next year, to compensate, Colombian growers managed to expand their coca production by more than 25 percent. The former Colombian "cartels" (a bizarre concept to begin with for this wildly competitive form of drug capitalism) have now turned into hundreds of more able and streamlined entrepreneurial groups. The capacity for making illicit cocaine in the Andes has reached about 1,500 tons annually -- a new record -- and some 150 times the region's peak capacity when the drug was a legal medical good at the start of the 20th century.

That's hardly progress. And that's not to mention the terrible violence, destruction, and corruption that accompanies the drug trade, sustained by our self-defeating prohibitionist policies.

Q: What role does cocaine play in the United States's current policies with Latin America?

A: Cocaine is still a weighty and volatile factor in inter-American relations. The burning issue today is, of course, the spiraling violence related to the routing of cocaine smuggling through northern Mexico -- not the book's focus, but still another negative impact of our now century-long prohibitionist policy on drugs. Lest people forget, this new geography of cocaine was born from our attacks on Colombian traffickers and their Caribbean air and sea routes. Cocaine still dominates relations with Colombia, with the merits and demerits of the repressive "Plan Colombia" still up in the air. Bolivia's current wave of coca nationalism is a vibrant response to the long-held U.S. policy of demonizing and combating the leaf and may point to our less antagonistic future with Andean coca and cocaine.

One hopes that President Obama, whom I admire for his rational and pragmatic outlook on most social issues, will be able, perhaps by a second term, to reform drug policies that have never worked, such as overseas interdiction. It has only compounded problems with drugs and aggravated relations with Latin America. American presidents have consistently lacked the political courage to address our impractical and ideology-driven drug policies. Obama should refocus the U.S. on the domestic issues behind recreational drug use and addiction and address the racial injustices and social harms spawned by our own punitive drug laws. Now that's "hopeful" thinking!

Q: What do you think about the book's cover?

A: Love it! UNC Press uses some great designers, and everyone I know has said it's strikingly creative. Of course, if it's really supposed to be a "brick" of Andean cocaine, readers are getting a fabulous deal at only $24.95! Just don't try to take it through customs . . . .