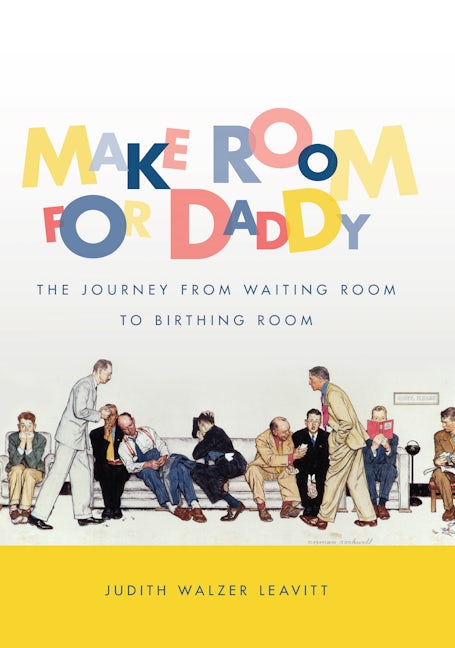

Make Room for Daddy

The Journey from Waiting Room to Birthing Room

By Judith Walzer Leavitt

400 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 72 illus., notes, index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-8078-7168-3

Published: August 2010 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-8783-7

Published: August 2010 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-7955-4

Published: August 2010

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2009 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

Judith Walzer Leavitt, author of Make Room for Daddy: The Journey from Waiting Room to Birthing Room, delivers an account of the evolving role of fathers in childbirth.

Q: Why have men been omitted from traditional histories of childbirth?

A:Historically, childbirth took place at home. The birthing woman was attended by her female family members, woman friends, and a midwife. Then, beginning in the late eighteenth century, male physicians began to attend urban middle class women in their homes. This trend to have medical birth attendants increased during the nineteenth century. Husbands waited outside the birthing room. Because men were excluded from the birth itself, historians -- including myself -- also ignored them when writing about the event. When childbirth moved to the hospital in the twentieth century, men still were not allowed to be with their wives. They waited in hospital waiting rooms, sometimes called stork clubs, while their wives labored and delivered without them.

Q: As a historian, why do you feel the subject of men and childbirth is significant?

A:As it turns out, despite being excluded from home and hospital birth rooms, laymen historically have been very involved in their wives' births. Emotionally they eagerly followed events inside the rooms and worried about outcomes. They also often had specific tasks -- like the classic image of men gathering wood for the fire to boil water -- and sometimes kept journals or wrote letters that today make it possible for historians to reconstruct events.

But even more important, childbirth is a central concern of all men and women because the event constitutes the basis for our very existence. Today, most partners of birthing women do participate in labor and deliveries and understand how joining together for this life cycle event is central to the couple's relationship and family building.

Q: Who do you hope will read this book?

A: I hope men and women of all ages and family configurations will find this history of men's participation in childbirth a fascinating and riveting story with meaning for their own lives.

Q: How did you learn about men's perspectives on birth?

A: I was doing research in a Chicago area hospital's archives when the archivist brought to my attention lots of "fathers' books," which were journals the hospital had kept in the fathers' waiting room during the 1940s and 1950s. In these books, the men wrote entries in which they poured their hearts out with the emotion of the time. They prayed to God and wished for male children; they gave each other advice. Then, when other men came into the room, they read what the men before them had written and wrote their own poignant messages. These books made me realize the importance of men's roles in childbirth and enticed me to write their stories. In broadening my research beyond the fathers' books, I sought other men's voices in oral histories, interviews, and men's writings. In addition, I used published writings in medical and nursing journals and in the popular press.

Q: When did men move from the waiting room to the labor and delivery rooms?

A: By 1938, half of American births took place in the hospital. At that time, and for a couple of decades thereafter, most men remained isolated in hospital waiting rooms while their wives labored and delivered. There was a closed door between the waiting men and their laboring wives. Some hospitals allowed the men to briefly visit their laboring wives; most did not provide this access until the 1960s. During the 1960s, most hospitals, under pressure from birthing women, laymen, the women's movement, and childbirth reform groups, admitted men into labor rooms, but not until the 1970s -- and in some hospitals the 1980s -- were the doors to the delivery room open to men. Beginning in the 1980s, men have felt enormous pressure to be with their wives throughout the birth process.

Q: How have the practices of childbirth and the role of men in childbirth changed throughout history?

A:This is the enormous question that Make Room for Daddy addresses. In brief, childbirth over time has become more medicalized, in the sense of having physicians involved and increasing the use of medications and medical technologies. In my previous book Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America 1750-1950, I traced the role birthing women played in bringing about these changes; in this book, I look at the roles the men played in the changes during the period of hospitalized childbirth, from approximately 1935 through the mid-1980s. Both men and women helped make birth more medical as they sought what they thought would be the benefits of modern medicine. This trend somewhat reversed after 1960 as the natural childbirth movement, in which both women and men participated, sought less intervention in the process of childbirth.

Q: How do these changes reflect the changes in family life and the shifting roles of men and women in the home?

A: During the twentieth century, marriages became more sharing and intimate as women lost some of their traditional female networks to geographic mobility and changes in work patterns. After the Second World War, the developing suburbs began to foster what one historian has called "domestic masculinity." This meant that middle class men began to adopt a small domestic role, usually around the raising of their children. Writers such as Benjamin Spock encouraged them to learn to diaper their babies and read to their children in the evenings. Men's roles in that mid-century period did not begin to approach anything we would today recognize as egalitarian. Nonetheless, as men played more of a role in home life, they recognized the benefits of doing so, and this made them more amenable to participating in childbirth too.

Q: What role do hospitals play in men's experiences surrounding childbirth? How has this changed over the years?

A: As birth moved out of the home and into medical institutions, practices changed dramatically. At home, women had been surrounded and helped by women they knew and with whom they had close personal relationships; in the hospital, women were "alone among strangers." Men had been excluded in both settings. But as they banded together in the hospital waiting rooms, in person, and through the fathers' books, men collectively found the courage to challenge hospital exclusion policies and ultimately came to share both labor and delivery with birthing women.

Q: How has the media affected our perception of the role of men in childbirth? What about books, particularly handbooks for childbirth and child-rearing?

A: The media and popular manuals for parents have enormous importance in childbirth. I'll give just one example. In the late 1950s, the Ladies' Home Journal ran a series of articles about childbirth, some of them revealing what they called "cruelty" in hospital maternity wards. The journal gave many emotional examples of women suffering at the hands of hospital policy -- including babies being held back until doctors arrived, women left alone in misery during the long hours of labor, and women being coerced into taking drugs they did not want. The bottom line was to urge hospitals and physicians to change their policies and allow the women's husbands to join them during labor to give them reassurance and comfort and, by their very presence, prevent unwanted practices. Many other outlets, too, encouraged men's presence during labor and delivery to comfort the birthing women, to cement the family bond, and to more deeply involve the men in their children's lives.

Q: What expectations do men today have about childbirth?

A: As in the past, individual men have individual reactions and expectations about childbirth. Most men do accompany their wives or partners into labor and delivery, although some voice great ambivalence about being there. But as men participate more, they find that some of their own needs around impending fatherhood are not yet satisfied by the hospital experience. This is as big a transition for men as it is for women, and each man brings his own point of view to the process. Hospitals are becoming responsive to the diversity in men's expectations, and increasing use of doulas -- lay birth attendants who support the birthing couple -- are helping both men and women achieve their expectations.

Q: What do you make of the growing popularity of the phrase, "we're pregnant"?

A:The phrase used to bother me, because, as a birthing woman, I was well aware that I was the pregnant one and physically felt the burden (and the delights) alone. But as I worked on this book and became more connected to the men's viewpoints, I changed my mind. I think the phrase reflects a positive recognition of the participation and cooperation of both father and mother.

Q: How do racial and class differences change the experiences and expectations of men in childbirth?

A: In my book, I was able to trace the developments around men's participation in childbirth in white and African American experiences. Hospitals until the mid-1960s were segregated by race and by class. Middle and upper class white couples who could afford to pay for private or semi-private rooms in hospitals had the earliest opportunities for men and women to share labor and delivery. Then, middle class black couples gained access to such sharing. Those poor white and black women who delivered in public hospitals -- literally often laboring on stretchers in the corridors -- had no such opportunity to be together.

Q: What kinds of problems or conflicts do men encounter in the delivery room? Do some feel unduly pressured to be there?

A:Today some men voice ambivalence or hostility toward being asked or urged to be present in labor and delivery rooms. They say they often feel like third wheels, hanging around with not much to do, not knowing where to stand or sit, and feeling no one is paying any attention to them. It is hard to know how many men feel this way. Most men still seem to find the experience awe-inspiring and exciting and don't want to miss it.

Q: What do you predict for the future of men and their experiences with childbirth?

A: History shows that hospitals are quite adaptable and try to satisfy their obstetric patients. I think they will continue in this mode and work to make men more comfortable during labor and delivery and help them find a place for themselves. In fact, hospitals have already demonstrated this. In the 1980s, many provided "birthing rooms," where the woman could labor and deliver in the same room with her husband in a friendly domestic environment. Men found this space very welcoming and continue to voice their appreciation for a hospital room that makes it easier for them to participate in labor and delivery. Also, a more expansive definition of family has in recent years helped to create a meaningful place for unmarried couples and for the partners of lesbians giving birth. The flexibility in birth practices today give birthing women's partners more opportunities to find the experience positive and valuable.