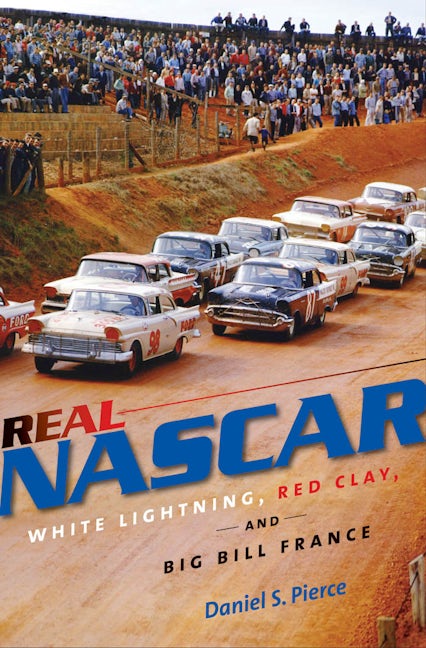

Real NASCAR

White Lightning, Red Clay, and Big Bill France

By Daniel S. Pierce

360 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 30 illus., notes, bibl., index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-4696-0991-1

Published: August 2013 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-9572-6

Published: August 2013 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-7397-2

Published: August 2013

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2010 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

Daniel Pierce, author of Real NASCAR: White Lightning, Red Clay, and Big Bill France, explains how a college history professor came to have one side of a Dodge Challenger bolted to his office wall.

Q: How did you get interested in NASCAR? Are you a longtime fan?

A:I grew up near a local short track here in Asheville but always denigrated stock car racing; that is until my conversion in August 1994 at Bristol Motor Speedway. My college roommate and best friend convinced me to go to a race with him there, and being a scholar of Southern History, I felt obligated to go see what all the hoopla was about. Needless to say, I loved it and immediately became a lifelong fan. I still go to at least two races per year in NASCAR's top division, try to go to as many local short track events as I can (Bowman Gray Stadium in Winston-Salem is a big favorite), and either watch the race on TV or listen to it on the radio when I'm traveling. I generally cheer for the old guys (guys my age), but love it when Kyle Busch does something outrageous.

Q: Why are NASCAR's fans so passionate and loyal? What accounts for the sport's appeal?

A: Part of the appeal, I believe, is that lots of folks think they could do this if they only had the right breaks. Most of us drive cars, and NASCAR drivers are more human in scale than football, basketball, or even baseball and hockey players, so there is this illusion that we're not really that different from them (trust me, they're not like you and me in lots of ways). The in-person experience at a NASCAR race (or even at most short tracks) is a powerful sensory experience. Television does not do the sport justice as it just can't communicate the intensity of sound, smells, and the almost overwhelming carnival atmosphere. Actually attending a race generally turns folks into fans.

A lot of traditional fans were drawn to racing in the 1940s and 50s as a way to escape the drudgery and regimentation of life in cotton mills and furniture factories. There's something about racing a stock car (or watching someone do it) that makes it an ultimate expression of freedom and individuality.

Q: Just how big an industry is NASCAR?

A:NASCAR has the second most lucrative TV contract of any professional sport and for the past ten years has generally drawn more than 100,000 fans to most of its races. A 2006 study by UNC-Charlotte economist John Connaughton estimated NASCAR generated over 27,000 jobs in North Carolina alone with an economic impact of $5.9 Billion annually.

Q: Did you face many challenges when writing this book?

A:There were a number. People are often unwilling to talk about illegal behavior, although it is interesting that they'll often tell what they did but won't tell you what someone else did. Fortunately, I found some folks who were pretty frank, and I was also able to find some important and revealing tidbits in published interviews that gave me insights into what was going on. Another problem is that NASCAR is a private, family-owned corporation that is highly protective of its image. Their records aren't exactly open to the public. Finally, a lot of NASCAR history is based on oral interviews. I've discovered that much of what has passed for history is simply not true. I had to go through lots of local newspapers and racing publications to separate fact from fiction.

Q: What role did bootleggers and moonshiners play in the early days of the sport?

A:When I first started doing research on NASCAR, I thought I would prove that the whole moonshine connection was overblown and exaggerated. As I put it in the introduction, however, "The deeper I looked, the more liquor I found." Bootleggers and moonshiners were at the very core of early Piedmont stock car racing and the early days of NASCAR. The illegal industry not only provided the most talented and successful drivers, but the best mechanics, car owners, promoters, and race track builders and owners.

Q: Who is William Henry Getty "Big Bill" France and what makes him unique among sports figures?

A:France is one of the most unique figures in all of sports history. He drove in the first major stock car race in the South, became a top driver in the late 1930s and early 1940s, started promoting races, and by the late 1940s became the top stock car racing promoter in the nation, created NASCAR and soon became its sole owner, became involved in ownership of a number of important tracks, developed an important feeder series to develop new talent, forged relationships with the auto makers that first put the sport on the national radar screen, built two of the most important tracks in the sport, crushed two attempts to organize a union by NASCAR drivers, negotiated one of the most important, and lucrative, alliances between a corporation (R.J. Reynolds Tobacco) and a professional sports organization in history, and personally ruled the sport with an iron hand for over twenty years. He was part of every major step in laying the foundation for NASCAR to become a major American sport and not just a Piedmont southern pastime. In the process, France—who arrived in Daytona Beach in 1935 virtually penniless—built both a sporting enterprise that is internationally known and a family fortune now worth billions of dollars.

Q: How long has NASCAR been considered a mainstream sport? Why has it struggled for respectability in both the world of motorsports and American sport?

A:The journey toward respectability has been a long one for NASCAR. Indeed, it's only been in the last 10-15 years that NASCAR has received the type of attention in the media accorded other major sports. Part of this struggle has been because the history of NASCAR is so rooted in gritty, working-class Piedmont culture and so strongly connected to the moonshine business. Early dirt-track races were pretty rough affairs, with excessive drinking, fighting, and overall unacceptable behavior common among drivers and fans. As promoter Humpy Wheeler once argued, the dirt racetrack in the 40s, 50s, or even 60s "was not the place you wanted your daughter to go." All this began to change in the early 1970s with the arrival of R.J. Reynolds and its marketing folks, television (particularly ESPN in the early 1980s), and the expansion of the sport into parts of the country outside the Piedmont South.

Q: How have American automakers influenced NASCAR? Why has such an emphasis been placed on the make of the automobiles?

A:One of the great attractions of stock car racing is fan identification. Fans not only identify with the drivers (who seem like themselves), but also with the cars which (at least until relatively recent times) looked (at least on the outside) like the cars they drove. Early on automakers discovered that if their make won stock car races, their sales increased. The phenomenon is known as "Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday." Ford was the first beneficiary of this phenomenon as its late 1930s and early 40s Flathead Ford V-8s dominated most early stock car racing. In the late 1940s, Oldsmobile received a boost due to the success of its "Rocket 88"s.

In the early 1950s, Daytona Beach driver and mechanic Marshall Teague formed the first formal agreement with an automaker when he gained the active support of Hudson. The success of the "Fabulous Hudson Hornets" driven by Teague, Herb Thomas, and Frank "Rebel" Mundy on the track and the boost in Hudson sales made Detroit sit up and notice what was going on down South. By the mid-1950s, the automakers were spending millions on race teams and promoting the success of their makes in major ad campaigns. Although Detroit came in and out and often played a disruptive role in the sport, Piedmont NASCAR fans forged lasting generational bonds to particular makes of automobiles. Indeed, by the 1960s most fans were committed to Chevy, Ford, Pontiac, Dodge, or Plymouth for life and would not dream of supporting a driver or owning a car of any other make. There are still traditional NASCAR fans who have yet to forgive Richard Petty for driving a Ford (instead of a Plymouth) in 1969.

Q: What was the controversy that surrounded the Mercury Outboard?

A:The owner/founder of Mercury Outboards, Carl Kiekhaefer, was one of the first major corporate sponsors in NASCAR. The perfectionist Kiefhaefer fielded as many as five cars at a time in races in 1955 and 1956, and his drivers won the Grand National (NASCAR's top division at the time) season points championships in both years. The problem Kiekhaefer and Mercury faced -- and one faced even today by sponsors - was that his team won too much. Fans became angry when his cars always won the race, and this had a detrimental impact on Mercury sales in the Piedmont South. Keikhaefer left the sport in 1957 never to return.

Q: World War II produced a new generation of mechanics. What kind of impact did they have on NASCAR?

A:Many of the most important mechanics in NASCAR history gained both training and experience through their military service in WWII. Partly as a result of their war experience, Smokey Yunick (who did his own mechanical work on the the B-17 Flying Fortress he piloted), Ray Fox, and Bud Moore ("an old country mechanic who loved to make 'em run fast") became the most important owners and mechanics in NASCAR during the 1950s and 60s.

Q: You say that NASCAR has its deepest roots in the Piedmont South. How do you define this area and why is locating its origins here so important?

A:I define the Piedmont South as the area roughly stretching from Richmond, Virginia through the mid Carolinas and Georgia and ending up around Birmingham, Alabama. It's the South of cotton mills rather than cotton plantations and red clay rather than black loam. I think it is important to situate the roots of southern stock car racing/NASCAR in this region because its growth and popularity was very much connected to the region's geologic and cultural history. The red clay makes for a great, relatively cheap to build racing surface, and the cultural interaction between mountain and foothill moonshiners and mill villages provided the bulk of participants and fans in the sport's early years.

Q: What is the single biggest misconception that the public has about NASCAR?

A:I think there has been a tendency to underestimate the intelligence of participants in, and fans of, NASCAR. A lot of people have looked at these individuals as ignorant rednecks. The people I've discovered were incredibly intelligent and creative. Junior Johnson is a great example. He comes across as this slow talking, slow moving, slow thinking bumpkin. The reality is much different, in fact, I think the guy is a genius; he was an incredible driver, had great abilities as a motivator of drivers and crew members, and is a far-seeing and astute businessman. In terms of understanding how to make a car go fast, he is probably without parallel. Indeed, when asked if he went to Detroit for advice on how to set up his cars, he responded, "No. Detroit comes to us." I don't think Junior Johnson has ever read a physics textbook, but I think he could probably write one.

Q: You talk about the "hell of a fellow" ethos that seems so vital to NASCAR culture. Just what is this?

A:This phrase was coined by W.J. Cash in his classic work The Mind of the South. Cash spoke of this male cultural ideal that developed in the rural antebellum South for a man to "Stand on his head in a bar, to toss down a pint of whiskey in a gulp, to fiddle and dance all night, to bite off the nose or gouge out the eye of a favorite enemy, to fight and love harder than the next man, to be known eventually far and wide as a hell of a fellow -- such would be his focus." This ideal of male attitude and behavior remained powerful into the twentieth century, although the ability to act on such impulses became increasingly limited. When the automobile became widely available in the 1920s and 30s, it was natural for young men steeped in this ethos to start racing one another. I think for a lot of working-class Piedmont men, stock car racing became one of the most attractive ways to express these hell of a fellow values and prove their manhood.

Q: How have women made a name for themselves in this male dominated sport?

A: Interestingly, women drivers were much more visible in the sport in its earliest days than they are today. In the late 1940s, promoters in South Carolina began organizing races for women called "powder puff derbies." As a way of attracting crowds, these same promoters encouraged the most successful women to compete in the main events. Bill France jumped on the bandwagon in the first year of NASCAR "Strictly Stock" racing in 1949. Sara Christian, the wife of a bootlegger, became the most successful of these women drivers and had several top-ten finishes in that year. Ethel Flock Mobley beat two of her three brothers in the first Daytona NASCAR "Strictly Stock" race. The longest lasting of the drivers, and most colorful, was Louise Smith who raced in NASCAR until 1952. While she generally finished in the back of the pack, she provided lots of thrills as her cars often ended up on their roofs -- "I needed wheels on top. I'd a drove a lot better."

By the early 1950s, however, the novelty had worn off, and encouragement and appearance money from promoters and from NASCAR began to dry up. A few other women drove in NASCAR's early races, but by the mid-1950s signs appeared in the infields of most tracks banning women -- except for the beauty queens who presented trophies and kissed the winner. This lasted until 1976 when Janet Guthrie made a four-year foray into the sport with some success. Many thought this would pave the way for women to become regular participants in NASCAR, but while some have competed sporadically since (and most local short tracks have regular women drivers) women remain a rarity in the sport. There is lots of current speculation that Indy Racing League star Danica Patrick will start racing in NASCAR, but no deal has been made as of yet, and 1949, sadly, remains the heyday of women in NASCAR.

Q: How has NASCAR changed since you became a fan and where do you think the sport is headed?

A:When I first became interested in the sport, NASCAR was very popular already but was on the cusp of explosive growth. A good example of the changes since then are exemplified by what has happened at Bristol Motor Speedway since the first race I attended there in 1994. In '94 Bristol was owned by a local entrepreneur and held about 70,000 fans. Today the track is owned by Speedway Motorsports Inc. (which trades its stock on the New York Stock exchange and owns eight major tracks) and holds 160,000+ fans. The price of tickets has changed as well, with the first tickets I bought costing $70 and current tickets running at around $120. The clientele has also changed, with lots of corporate types around, large corporate tents to entertain clients and employees outside the track, and over fifty luxury skyboxes.

When I first became a fan, most of the top drivers were from the Piedmont South and most of the tracks were still in the region. Now most of the drivers are from the far west or mid-west, and there are major tracks in almost all of the nation's major media markets. Several of the old Piedmont stand-by tracks have been shuttered. A television contract worth billions of dollars to the sport now ensures that fans all over the country can watch the weekly races and tune into dozens of cable shows devoted to the sport.

Some traditional fans feel alienated as the sport has moved further from its geographical and cultural roots. The death of Dale Earnhardt in 2001 and the moving of the traditional Labor Day weekend race from Darlington, SC to Southern California in 2004 caused some of these fans to lose their intense passion for the sport. At the same time, lots of new fans have come on board, although there is some question about whether their NASCAR fandom will be just a passing fancy.

The current recession, the over-construction of "cookie-cutter" 1.5-to-2 mile tracks that have produced relatively boring races, the plain-vanilla personality of many of the current stars, the lack of noticeable differences between makes (except for decals) in the current cars, and questions about the talent, judgment, and genuine love for the sport of the third generation of the France family now running the sport are causes for concern, reflected in declining ticket sales and lower TV ratings. However, NASCAR has a wonderful core product and has weathered storms this serious in the past.

Q: You're a North Carolina resident. Are you sporting any of the state's specialized stock car racing theme plates on any of your vehicles?

A:Haven't done this yet. My first book was on the history of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, so right now my vehicles have "Friends of the Smokies" tags. I do have the whole side of a Caterpillar-sponsored Dodge (once driven by Dave Blaney in NASCAR's top division) bolted to my office wall (I won it in a raffle). I think I can safely say it's the only such display in an academic office in America. I also have a Dale Earnhardt (Sr.) sticker on my 1990 Ford Ranger truck, and I'm not ashamed to say that I cried when he died.