The Color of Christ

The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America

By Edward J. Blum, Paul Harvey

352 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 19 halftones, notes, index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-4696-1884-5

Published: August 2014 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-3737-5

Published: August 2014 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8275-2

Published: August 2014

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright (c) 2012 by the University of North Carolina Press. All rights reserved.Edward J. Blum and Paul Harvey, authors of The Color of Christ: The Son of God and the Saga of Race in America, discuss how Americans remade the Son of God visually time and again into a sacred symbol of their greatest aspirations, deepest terrors, and mightiest strivings for racial power and justice.

Q: Why does Jesus's race matter in America?

A: Race matters in every facet of American life. And religion matters deeply in American life, as well. The two collide when we think about Jesus's race. There, race and religion have formed a tight knot and the historical outcomes of picturing Jesus as white or black, brown or red have been at times horrific and at other times heavenly. When slaves and slave masters battled over the morality of bondage, they paid attention to Christ's race. When Native Americans struggled with whites over land rights and sexual interactions, they zeroed in on the race of Jesus. When visionaries sent letters to Abraham Lincoln saying that Jesus had come back to save the Union, they emphasized that Jesus was a white warrior setting out to destroy black slavery. When Klansmen dressed in white and burned crosses in their opposition to blacks, Jews, Catholics, and socialists, they did it all in the name and supposed race of Jesus. When civil rights activists like Martin Luther King Jr. tried to undermine the social system of segregation, they struggled over the race of Jesus. And when Barack Obama ran for the presidency in 2008, comments about the race of Jesus almost cost him the Democratic nomination. Today, as Americans watch The Passion of the Christ, laugh at displays of Jesus on South Park, read with wonder Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code, sing with The Killers that "he doesn't look a thing like Jesus, but he talks like a gentleman," or pray softly in churches with Jesus imagery above them, they cannot avoid the links between race and religion in the form of Jesus. Put simply, to understand the history of race and religion throughout American history and in today's politics and culture, there is no better way than through the struggles over the color of Christ.

Q: What, if anything, does the Bible say about Christ's body in descriptive terms?

A: The Gospel narratives of the Bible say nothing about the physical appearance of Jesus. There is nothing about his hair, his skin, his nose, his beard, or his eye color. In fact, the gospel writers say very little about any bodies except when ailments or illnesses are involved. John the Baptist draws attention, but for the kinds of clothes he wore and the foods he ate. Christ's body is at times represented as weary when he fasts, as torn when he's crucified, and as newly made with the resurrection. The piercings of his hands prove that he came back in bodily form. For all their detail about sayings, healings, and movements, the Gospels refuse to give any indication to what Jesus looked like.

Some readers of the Bible have tried to determine Christ's physical appearance from passages in Daniel and in Revelation. In the first chapter of Revelation, the author writes that he saw a man whose hair was "white like wool, as white as snow," and his eyes "were like blazing fire." To some, this description presents Jesus as looking like an elderly African American (white wooly hair). But very few folks see it this way. The writers of the Bible had their own obsessions, but race was not one of them. That's our modern obsession.

Q: What color was the first American Jesus?

A: Jesus became an American icon in the early 1800s. Before then, when Americans "saw" Jesus, they witnessed blinding and radiating light. Lightness, however, was not whiteness. And even when Jesus was painted as white from Moravians, they and their Indian converts focused almost exclusively on Christ's blood. It was his bloody redness that mattered most in the 1700s.

Q: When did the white American Jesus first become prominent?

A: Americans en masse began to see and produce Jesus as white only after the colonial period, after the Great Awakenings, and after the American Revolution. It was a time of great concern. Americans worried about what the nation would be religiously after church disestablishment with the Constitution; they increasingly struggled over slavery as the South expanded its cotton kingdom; they were networked together more tightly through new roads, canals, railroads, newspapers, and goods; and they debated the morality of driving into Native American lands. In these decades, white Protestants began printing images of Jesus as white and sending them throughout the nation. It was at this moment that a white Jesus was first used to try and bring unity and purpose to the young nation.

These decades also gave rise to the first Americans who challenged the whiteness of Jesus. William Apess, a Native American in New England, was the first to explicitly denounce the white Jesus as an emblem of white power. Ridiculing whites for oppressing African American and Native Americans, Apess insisted that whites knew that Jesus was not white, that he was "a man of color." Hardly anyone at the time listened.

Q: You say that immigration and global imperialism impacted depictions of Christ. How so?

A: Before the Civil War, just about every American identified Jesus as Jewish and as having brown hair and brown eyes. Race theorists of the antebellum age claimed that Christ's Jewishness, in fact, proved his whiteness. The main exception of the era was Joseph Smith and early Mormons who envisioned Jesus as white with blue eyes. They may have done this to establish their own whiteness, because so many Protestant Americans attacked them for their new religious beliefs and values.

But from the 1880s to the 1910s, the Jewishness of Jesus was challenged. Lots of white Americans began to fear Asian immigrants and the massive numbers of southern and eastern Europeans swelling into the nation. Nativist white Americans worried about the Judaism, the energetic Italian Catholicism, and the various political backgrounds these folks brought. So a movement grew to whiten Jesus even more. Some everyday theologians, some Klan members, some New York lawyers, and some artists determined that they needed to transform Jesus from Jewish and Middle Eastern to be European or American. Some fretted over the change, but felt it was better for the nation to see Jesus this way. They began painting him with blond hair and blue eyes. In the United States, white supremacists like Madison Grant called this Jesus "Nordic." In Germany where a similar process had been under way, Nazis called this Jesus "Aryan."

Q: What role did Hollywood play in defining the appearance of Christ?

A: At first, Hollywood needed Jesus. When the film industry began in the early 1900s, it was damned as immoral by many Americans. Films were seen as raucous distractions from real life and where impressionable youth learned to idolize criminals and violence. A number of early filmmakers decided that they needed to court churches so that films could be seen as helpful to the morality of the nation and to missionary work. If they could get church women and men to buy into the cinema, they could convince everyone that films were good for the nation. So they turned to Jesus movies.

D. W. Griffith and Cecil DeMille both directed early Jesus movies. Accused of racism because of Birth of a Nation, his film that glorified the Ku Klux Klan, Griffith made a movie about intolerance and featured Christ's love as a main part of the story. Griffith even cast the actor who played Robert E. Lee in Birth of a Nation to now star as Jesus. Cecil DeMille directed The King of Kings in the late 1920s. It was just after World War I had ravaged the globe, and Americans were vigorously debating what the nation should be like politically, racially, and religiously. DeMille offered a white Jesus who was the king who rose above all other kings.

With time, however, Jesus started needing the film industry. Hollywood became the arbiter of what was beautiful, cool, and exciting. Americans focused more and more on physical beauty and youth. As Hollywood focused on younger, sexier, and tanner men and women, Jesus became younger, sexier, and tanner throughout the century. The age of actors who played Jesus came down, and directors started zeroing in on blond hair, blue eyes, and chiseled tan chests.

Hollywood has also mattered because it provides the backdrop for most Jesus films. Southern California has become a surrogate sacred geography. The state's hills, sands, and mountains are supposed to look like the Middle East. The actors and the extras are taken from the hordes of wannabe stars in Hollywood, and hence the characters are typically white and often in good shape. As a physical space and as a culture maker, Hollywood has transformed what people think Jesus, those around him, and the terrain of his life looked like.

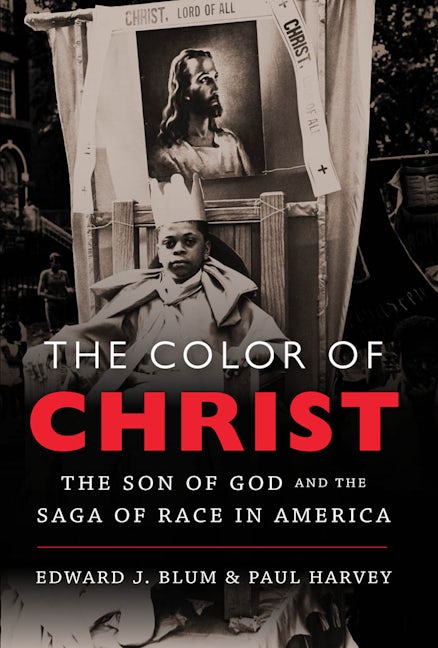

Q: Warner Sallman's "Head of Christ" (1941) happens to appear as an element on your book's jacket. Who was Warner Sallman and how did he revolutionize Jesus imagery?

A: Warner Sallman was the son of European immigrants to Chicago in the 1890s. He was a commercial artist who decided to enroll at a Fundamentalist Bible College and use his talents for the kingdom. A dean there encouraged him to paint a new head of Christ, one that was not so "effeminate." After a charcoal sketch, Sallman's 1941 "Head of Christ" was produced and marketed by a small publishing firm for the Church of God. It was a relatively simple head of Christ. Jesus had blondish hair that fell below his shoulders. He had blue eyes and he gazed into the distance. It looked like a yearbook portrait and had nothing in the background.

The image exploded into the nation and the world. By the 1980s, it had been reproduced more than 500,000,000 times. Estimates range that it has now been reproduced more than 1 billion times and is the most reproduced image in world history. It was embraced by whites, blacks, Native Americans, Protestants, Catholics, Mormons, and throughout the globe. It influenced castings for Jesus movies on the small and silver screens. Sallman's "Head of Christ" one of the most fascinating stories in American history. The new worldwide image of Jesus did not come from Hollywood producers or from Harlem painters. It came from a small-time Fundamentalist from the Midwest.

Q: Why is one's childhood experience of the color of Christ so important and so problematic?

A: We learn so much before we can reason, comprehend the words spoken around us, or speak ourselves. Try remembering when you first saw your parents? We cannot do it, because our sight predates our memory. Before children can read the Bible, they see images of Jesus. Before they wrestle with theological problems, they behold sacred icons.

Either in a book, at church, in the living room, or on television, children look at these images and they experience adults treating the images with some kind of reverence. Deep down in their psyches, many American children learn to associate the divine with the white race. It is a psychological feeling that does not have to become a proven intellectual fact. When Warner Sallman's "Head of Christ" is sometimes presented to 2 and 3 year olds, some shout out, "It's Jesus!" They express a feeling of closeness to this person they have never met, whose story is in a Bible they cannot yet read for themselves, and who lived centuries ago. This may help explain why white Christians have historically cared more about the wellbeing of other whites, because deep down they associate whiteness with godliness.

When white Americans turned to images of Jesus to teach the faith, they zeroed in on children and as they did they drastically altered their approaches to Christianity. Before the Civil War, American Protestants purposefully used images of Jesus to "entice" and "tempt" children. Then with movies, adult Christians tried to "allure" children with entertaining sagas of Jesus. So to reach out to children, Americans incorporated marketing strategies that seemed to play more into traditionally the devil's devices. The attention to children and the use of Jesus images has been one of the crucial factors in transforming the United States into the world's leading producer of Christ imagery.

Q: In your Introduction, you state that the "The white Jesus promised a white past, a white present, and a future of white glory." What do you mean by that?

A: The Bible says that Jesus is the "alpha and omega," the beginning and end. He existed from the creation of the world, he redefined the world with his life, death, and resurrection, and he will sometime come back again at the end of history. When Americans made him white, they gave a racial spin to creation, to redemption in the form of Jesus, and to the future Apocalypse. This is crucial because it allows white people to see whiteness and racial categories as everlasting. Even though science, history, and anthropology has shown that races are cultural and social constructions, Americans can continue to believe that a "white race" has always been. The whiteness of Jesus has also has led many Americans to be fearful of interracial sexuality and marriage. It was not until 1967 that the Supreme Court ruled that states could not bar interracial marriage, and for some Americans the idea of white superiority now and for the future is tied to their children and to their notions of what Jesus looked like.

Q: Why does place/geography matter in the ways that Christ has been depicted?

A: Place and space are essential to how we see people. Background information provides the cues for how we interpret a person. For instance, a sad-looking child in a classroom may make us giggle. A sad-looking child with a war-ravaged street in the background will leave wholly different feelings. When it comes to race and religion, the background markings influence what we think of Jesus. When placed in a desert or mountainous region that is supposed to mimic the Middle East, Jesus is distanced from America in some ways. He's the savior "born across the sea," as Julia Ward Howe famously wrote in "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." The refusal to see Jesus as distant is one of the things that makes Mormonism so fascinating. The Book of Mormon brings ancient Jews and Jesus to the Americas long before Columbus or the Puritans. His holy whiteness was there before European colonists collided with Native Americans. By placing Jesus in America and by visualizing that which is good as white, Mormons expressed another facet of how American religion could be used to imagine a white past that transcended known history.

The lack of places has mattered too. Warner Sallman's "Head of Christ" has nothing in the background: no camels, no mountains, no other people. It's just a cameo of Jesus. This allows viewers to bring Jesus into their specific moment without any rupture. This Jesus could be a photograph in a high school yearbook, a family picture on the wall of a suburban home or an inner city apartment, or next to a catalogue in an Oklahoma farm.

Geography and place are also reasons that some Americans are better at considering Jesus as possibly black, rather than Native American. Since Africa is close to the Middle East, and since the gospels tell of Christ's parents hiding him in Egypt, some Americans have thought this could mean that Jesus had a black appearance. When liberation theologians have then cried out that "Jesus was black," some have used the Bible's geography as part of their proof. The same geographical connections have not been made for Native Americans. Since North and South America are geographically separated from Israel, it has been harder to create a land link for Indians to Jesus. So when Native Americans have typically looked to Jesus as an Indian, they sometimes associate him to another sacred force--Peyote, for instance,--or reincarnate him in the present--such as in Wovoka and his ghost dances, or see Jesus as somehow a red and white man, as Black Elk did.

Q: What connection, if any, is there between European depictions of Christ in artwork and images of Christ produced in the United States?

A: When Americans started churning out images of Jesus in the early 1800s, they used European artwork for their models. Before that, Protestant Americans were largely iconoclastic—that is to say, the Puritans (for example) thought it was unbiblical to have images of the divine and thought images of Jesus were part of the evil of Catholicism. During the colonial years, French Jesuits and Franciscans in the Southwest tried out a variety of images for the Natives they were trying to convert. In some cases, Natives brought the images into their lives, but in other cases, as in the massive Pueblo Revolt of 1680, they rejected them. During the revolt, depictions of Jesus could be found destroyed, dismembered, and sometimes profaned with excrement.

But the spread of Jesus images for mainstream Protestant Americans was basically a nineteenth-century phenomenon that grew more out of the mass culture of reproduction than it did "high" art. In the twentieth century, though, everything changed. Americans went from importers of Jesus imagery to exporters. American images started to rival those from the European Renaissance for fame. The Warner Sallman "Head of Christ," born in America, remains dominant, not only in America but worldwide. Sallman's Jesus became the inspiration for how film directors portrayed Jesus, and missionaries have carried this look throughout the entire world. In fact, the most-watched film in world history shows Jesus looking like this. Even when comedians look to mock conservative Christianity, they parody Sallman's image. Ironically, the jokes reveal and further the ubiquity of the image and how American art has come to influence worldwide visions of Jesus.

Q: When did jokes about Jesus and his body first appear? What purpose do they serve?

A: The first mainstream jokes about Christ's body came in the 1970s. Two of the funniest television shows ever toyed with Jesus jokes: All in the Family and Good Times. The 1970s were that weird time after the Civil Rights movement had been in full force but before political correctness made Americans fearful of racial jokes. It was the time between the economic growth of the 50s and the 60s and the unregulated Reagan 80s.

Both shows played fast and loose with jokes about racial, gender, and class stereotypes, and both of them included jokes about the body of Jesus. In fact, the second episode of Good Times was all about what Jesus looked like and whether it was okay for J. J. to use "Ned the Wino" (a local black drunk and prophet) as his artistic inspiration for a black Christ. The poor black family had to decide whether the white Jesus of their past would stay on the wall, or would the new black painting replace it.

Then in the 1990s and twenty-first century, jokes about Jesus and his body went into overdrive. In part, this was because of new arenas for humor--like Comedy Central--and in part this was because of how religion animated the culture wars. Some Americans wept as Jesus was brutalized in The Passion of the Christ, but others laughed as a paltry, silly white Jesus who fought the devil on South Park. Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert routinely use the image of Jesus as white for comedic effect, whether an animated white Jesus is defending Easter by shooting at his liberal foes on the The Colbert Report or an image from The Passion of the Christ is mocked in Stewart's book Earth: A Visitor's Guide to the Human Race.

Jesus as black is also a big part of American humor culture, but less for subtly and more for shock value. Films like Dogma joke about Jesus being black when bitterly laughing about racism in America. For black Americans, Christ's body is used as a joke for a bunch of reasons. Sometimes it's used to make points about generational gaps; sometimes it's used to pick on church people for being passive or hypocritical.

Turn just about anywhere in today's comedic culture, though, and you'll find jokes about Jesus and the jokes rely on concepts of his body. Perhaps the jokes are there because the problems of race and racial antagonism have not been fully resolved by the civil rights movement, by the government, or by Jesus.

Q: What kinds of myths surrounding Christ do you hope to dispel?

A: Our book takes on three main myths. First, there is a myth that humans create God or gods (especially Jesus) in their own image. This myth claims that people invariably represent Jesus to look like themselves. So whites make a white Jesus, blacks a black one, Asians an Asian one. But American history shows this is not true, and the myth hides how much racial groups have interacted and affected one another throughout U.S. history. No racial group in the United States has been separate enough to form distinct and impenetrable religious cultures. Moreover, lots of people have worshiped Christ figures that look nothing like them. For centuries, African Americans and Native Americans embraced white images of Jesus, debated them in their midst, and tried to replace them but generally did not. The myth hides the powers of money, of technological access, and of production capabilities. Slaves did not have the time or the manufacturing power to make or market pictures of Jesus as a black man, but they were inundated with images of white Christ figures. And then it gets even more complicated. When the white Jesus helped slaves run to freedom, he was defying white supremacy. So even racial images can be used to work against racism.

The second myth is that the United States has always been a "Jesus nation" or a "Christian nation." When we take seriously discussions of the race and color of Christ, we find that Jesus has been a lightning rod for struggle, conflict, and tension. For every occasion where someone makes Jesus into an icon of entrepreneurial salesmanship, as Bruce Barton did with his bestselling book of the 1920s The Man Nobody Knows, there are other Americans who have made Jesus a lynch victim (like W. E. B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes did in the 1930s), as a Native American who promised the defeat of the whites and the return of the Buffalo (as Wovoka did), or as a socialist who would get beat up by American mobs (as muckraker Upton Sinclair did). Jesus has not defined American culture; he has purely been at the center of the titanic and oftentimes bloody struggles over what the culture would be.

The third myth is that liberation theology emerged in the 1960s and was primarily a northern, black male phenomenon. This myth went into full blast during the Reverend Jeremiah Wright debacle of the 2008 presidential campaign when he could be heard on cable television and YouTube videos shouting "God damn America" and "Jesus was black." Media outlets searched for the genesis of these ideas and they turned to the 1960s. They located the work of James Cone as most influential and connected him to Wright and then Wright to Obama.

But liberation theology has a much longer history, and that history included Native Americans, women, and whites far more than the short history lets on. As early as the 1830s, some white Americans, black Americans, and Native Americans challenged expressly the whiteness of Jesus and several presented Jesus as on the side of disempowered people. In the present, there are many non-blacks who use darkened images of Jesus and some white artists even create them. Janet McKenzie is a case in point. Her "Jesus of the People," which presents Christ as looking African American, Native American, and feminine, is heralded throughout the United States, and McKenzie is a white woman from New York who was raised Episcopalian.

There has been nothing simple about the color of Christ in American history, and all of the various stories show the nation in its beautiful complexities, terrible tragedies, and hopes to somehow make the world a better place.