Give My Poor Heart Ease

Voices of the Mississippi Blues

By William Ferris

320 pp., 8 x 9.5, 45 illus., 1 map, bibl., index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-4696-2887-5

Published: February 2016 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-9852-9

Published: February 2016 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8268-4

Published: February 2016

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright (c) 2009 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

William Ferris sings the praises of Mississippi blues musicians

Q: In the introduction to Give My Poor Heart Ease, you mention that "While I may live and work in other places, my real home is the farm. It is my spiritual compass." How so? And what was it that ultimately led you away from your family's farm and down Highway 61?

A: Growing up in an isolated rural community with the black and white families who lived near my home shaped me in deep, lasting ways. Stories told by my grandfather, books read aloud by my mother, and hymns sung at Rose Hill Church are memories that to this day are incredibly vivid. These voices shaped my identity in deep, lasting ways.

What ultimately led me away from my family's farm was education: first to Brooks School in North Andover, Massachusetts, then to Davidson College in Davidson, North Carolina, to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, to Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland, and finally to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Earl MacCormac, my philosophy professor at Davidson College, later told me that I had "more degrees than a thermometer."

While these schools were far from my family's farm, each in their own way helped me tack a course back down Highway 61. While at Brooks School in the late fifties, I began a pattern of recording and photographing musicians each time I returned to the farm. As a graduate student in folklore at the University of Pennsylvania in the late sixties, this work became the focus of my dissertation. It was also at the University of Pennsylvania that I began to use film to document the blues worlds in which I found myself increasingly immersed.

Q: You began collecting images and recordings for this book at a very young age. How old were you when you began? What time span does the book cover?A: I began taking photographs at the age of twelve when I was given a Kodak box camera with a flash attachment for Christmas. I took my first black and white photographs of my family at my grandmother Hester Flowers's Christmas dinner table in Vicksburg, Mississippi, shortly after unwrapping the box in which my camera came. I later took photographs of Rose Hill Church baptisms in Hamer Bayou and in a pond near the church. And I took photographs of my family at our home. The time span in my book is from the late 1960s through the mid 1970s. As my work evolved, I returned each year to visit musicians who were my friends. The films on the DVD with my book capture performances by speakers and singers like Mary Gordon, Reverend Isaac Thomas, James Thomas, and Wade Walton, first on Super 8 black and white film shot in the late 1960s with a wild sound track, and later on 16mm color film shot in the mid 1970s with a synchronized sound track.

Q: How does this book differ from your previous book on the blues, Blues from the Delta?

A: My original idea was to "update" Blues from the Delta by adding more detail about my blues research and the artists with whom I worked. The more I thought about it, the more I felt this would be a stale rehashing of an earlier book. As I looked through my transcriptions of interviews that I had done in the late sixties, I felt that the real book lay in "freeing" the voices of each speaker and letting them tell their own story. In effect, I decided to change the book's perspective from that of a white scholar talking about music to that of black speakers describing their lives and how music shaped their worlds. This approach allowed me to focus on the rich language of each speaker and to capture each persona by using a series of dramatic monologues, a form that I discovered throughthe fiction of Ernest Gaines, Alice Walker, and Eudora Welty.

Q: This book is intensely personal, both in your approach to it and in your subjects' willingness to reveal themselves to you. It offers an extraordinary window into black churches, house parties, barbershops, radio stations, cemeteries, and the list goes on. How did you manage to get such a candid take on the world of the blues? And what kinds of lessons did you learn along the way?

A: I think the candid expression of feelings by each speaker in my book reflects in part their and my shared roots in Mississippi. On an important level, I was one of them, and my presence in their homes indicated my commitment to telling their stories. There was an implicit understanding that I was writing a book that would relate their story in a clear, unvarnished way. Once the tape began to run, their voices followed in truly amazing ways. They felt comfortable with me, they trusted me, and I, in turn, felt an obligation to share their lives through "the book" about which we spoke.

I also learned that moments captured through media are never fully heard or seen until later, when the photograph is developed, the tape played back, the filmviewed. Each time I hear these recordings, look at the photographs, or watch the films, I notice new details that remind me that these worlds of storytelling and music are richly textured and never stop speaking to me.

Q: Why did you decide to enhance the book with a CD and DVD? Ideally, how would you like your reader to experience this multimedia introduction to the blues?

A:Thanks to the marvel of technology, folklorists today can have their cake and eat it too. We can merge the printed word with sound recordings and motion pictures in ways that make this book dynamic and exciting. The reader of my book first meets the speakers as he or she reads their narrative and sees their photographs. They then hear each person's voice as they speak and sing on the CD, and they come face to face with the speakers and singers in films as they perform.

As a folklorist, I used sound recordings, photography, and film to capture the full impact of stories and music. Until now, however, I never had the luxury of merging all of these media into a single package. The CD and DVD deepen the relationship of the reader to the book. Through sound recordings and film, they intensify the relationship of the reader to each speaker and allow the reader to meet the speakers in significantly expanded ways.

Q: Other than in the introduction and framing remarks for each section, you chose not to include your voice in the published text or in the films and sound recordings that accompany the book. Why not?

A: I feel that this is a book about each of the speakers, and my own voice is important only as it describes how we met and sets the context of our visit. I believe that the uninterrupted narrative voice of each speaker constitutes a folkloric version of the dramatic monologue in literature. Through the narrative voice of a single speaker, poets and writers like Robert Browning, Ernest Gaines, Alice Walker, and Eudora Welty capture intensely powerful moments in their work. I try to achieve a similar effect by framing each section of the book with the voice of the speaker or speakers whom I recorded.

Q: One of your first interview subjects was your family's black housekeeper, Mary Gordon.Shortly before her death, she said, "You know, you are my white child." How did your special bond with Mary Gordon influence your work?

A: Growing up in a home where I spent many hours each day with Mary Gordon was an important part of my childhood. Her voice, her sense of humor, her stories, and her hymns were familiar, beloved parts of my experience. In many ways, this book is, by extension, a tribute to the history and culture of Mary Gordon. While she was an important part of my family, she also had an experience vastly different than my own. Her ancestors were slaves who worked the land around our home. Her ties to both the Rose Hill community and to Africa shaped me in profoundly important ways.

Q: Some of the most arresting images in the DVD are the scenes from Parchman Penitentiary, where the inmates of the Mississippi penal farm chop wood to the rhythm of work chants. How did you twice gain access to "Camp B," one of the largest black camps in this segregated system?

A: I was never sure how or why I was allowed into Parchman's "Camp B," and I never asked. Set apart from the main complex of Parchman, the camp is located several miles to the north east of the town of Lambert, Mississippi. On my first visit, I thought that I might have been mistaken for another visitor who was coming on an official visit. In both cases, however, I explained that I was writing "a book" on music and wanted to record prison work chants. The officials accepted this explanation for my visit and allowed me total access to the inmates. During my first visit in the late sixties, I recorded andfilmed work chants outside the prison buildings and a sermon by a white evangelical preacher in the dining hall that was followed by a capella gospel singing led by an inmatenicknamed "Flat Top" who sang with a beautiful high pitched tenor voice.

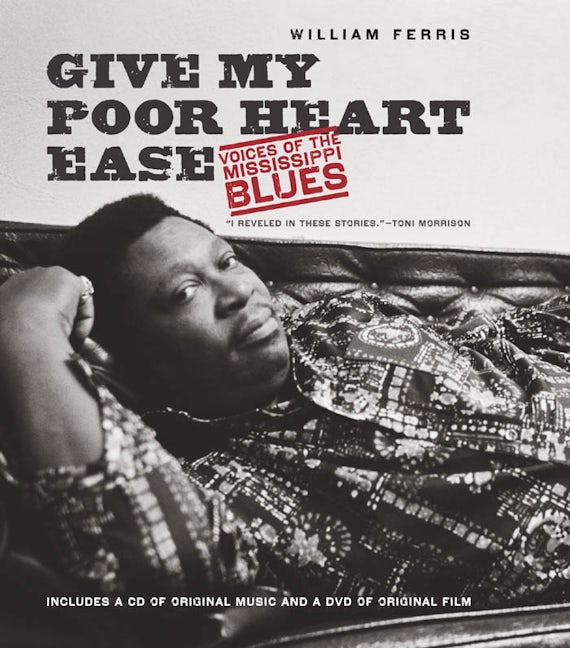

Q: B.B. King is featured on your book's cover and you have said that he is emblematic of all blues musicians. What will we learn from your book that we might not already know about this man whose name is synonymous with the blues?

A: B.B. King has a rare gift of humility and human warmth. In this interview he describes his childhood years and explains that his career as a blues singer is his way of reaching out to audiences whom he sees as his extended family. The genuine warmth that King brings to his musical performances allows him to communicate with fans throughout the world. From Indianola to Moscow and beyond, he touches the hearts of his audiences in profound ways.

We also learn that King moved from church music to blues when he discovered that blues fans were willing to pay to hear his music. And in his career as a bluesman, King turned to jazz performers like Django Reinhardt, as well as to blues performers like Lonnie Johnson for his inspiration.

Q: Are there any blues greats that you're still hoping to interview?

A: While I interviewed him earlier, I would love to spend more time with Bobby Rush, one of the most amazing performers I have encountered. I regret never interviewing Bo Diddley before his death. We visited over breakfast at Smitty's Restaurant after his last concert in Oxford, Mississippi, and spoke about his childhood in McComb, Mississippi. He explained how he learned to play the one-strand-on-the-wall, also known as the diddy bow, from which he took his name.

Q: How has the blues world changed in the last forty years?

A: The blues world has changed dramatically over the past forty years. The most startling changes have taken place in the Mississippi Delta, where much of this book is set. The B.B. King Museum in Indianola, Mississippi is a thirteen million dollar facility that pays tribute to B.B. King and to the rich history of blues in the Delta. A steadily growing number of blues markers establish blues trails where visitors can learn about the homes, clubs, and graves of celebrated blues artists. And blues clubs in towns and cities throughout the Delta feature live music performed by local artists each week.

Blues are also featured at the Grammy Awards, in House of Blues clubs, on television, and in feature films by directors like Martin Scorsese. Townes Van Zandt once remarked that "There are two types of music: blues and zippedydoodah." The musical landscape of our world today is deeply marked by the blues. And painters, photographers, poets, and writers are inspired by the blues in their work. Classical composer Lawrence Hoffman's "Blues For Harp, Oboe, And Violoncello" reflects his impressive knowledge of both country and urban blues styles.

It is moving and a bit surprising to think how a music that began in isolated, rural Mississippi has transformed our consciousness. The music helps us deal with tragedy and sadness in a positive, healing way.

Q: Who is on your watch list of new blues artists?

A: New blues artists include the children of important blues musicians. Pat Thomas in Leland, Mississippi, is following in the footsteps of his father James Thomas. He recently released a CD of his recordings and also makes clay sculpture of birds, animals, and human faces that are inspired by his father's work.

Shemekia Copeland, daughter of singer Johnny Copeland, has established an impressive musical career and is following in her father's footsteps. And Otha Turner's granddaughter Sharde Thomas is continuing the fife and drum musical tradition of her grandfather.

Q: What advice would you offer a young folklorist or documentarian or anyone aware of a "world waiting to be noticed"?

A: My counsel to students is to follow your heart. If you love what you do, you will do it well. There are so many worlds "waiting to be noticed." We simply have to open our hearts and our minds and listen to the voices who are waiting to speak with us. These voices are like sign posts along a highway that will lead us on a journey of discovery. It is exciting to pursue this work, to throw your full energy into capturing and understanding the worlds you pursue. The work will become a lifelong journey and will shape you in lasting ways. It makes you a better, more sensitive person.As you learn to walk in the shoes of others, you experience the double consciousness that blacks have understood for generations.

Q: I've heard that your book is the inspiration for a theatrical production. When can we look forward to seeing it?

A: University of North Carolina theatre producer Joseph Megel and folklore students WhitneyBrown and Ashley Melzer have created a stage production based on the speakers in this book. The production will feature a series of readings enhanced with field recordings, photographs, films, and live performances that will premiere during the comingyear.

And an exhibition of the photographs in the book will open at the Ogden Museum in New Orleans in conjunction with the 2010 New Orleans Jazz Festival.