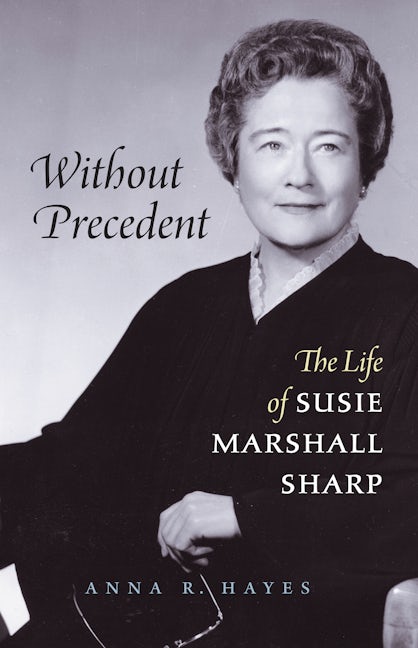

Without Precedent

The Life of Susie Marshall Sharp

By Anna R. Hayes

576 pp., 6.125 x 9.25, 20 Illus., notes, bibl., index

-

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-4696-4194-2

Published: December 2017 -

E-book PDF ISBN: 979-8-8908-8190-8

Published: December 2017 -

E-book EPUB ISBN: 978-0-8078-8781-3

Published: December 2017

Buy this Book

Request exam/desk copyAuthor Q&A

Copyright(c) 2008 by the University of North Carolina Press.All rights reserved.

Anna R. Hayes on the unprecedented career of North Carolina Chief Justice Susie Marshall Sharp.

Q: Who was Susie Marshall Sharp, and why was she so extraordinary?

A: Susie Sharp was a pioneer among women in the legal profession. When she began her career in 1929, women attorneys of all sorts were extremely rare, and, as a female trial lawyer, she was one of a bare handful in the state and the nation. In fact, for the first 17 years of her law practice, women in North Carolina were not even allowed to serve on juries. When she was appointed to the superior court bench in 1949, the idea of a woman judge was so unusual that one newspaper reporter, despite knowing that the Judge's name was "Susie," was shocked when he saw her, and said that he had expected to see a man by that name.

As a trial judge, Susie Sharp exploded the stereotypes and did such a good job that when Governor Terry Sanford named her to be the first woman on the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1962, the appointment met with universal acclaim. To her long list of "firsts," she added another in 1974, when she became the first woman in the United States to be elected chief justice of a state supreme court.

Q: How did you get the idea for this biography?

A: Growing up in North Carolina, I became aware of Susie Sharp at a very young age. Long before I knew that I would become a lawyer, I was familiar (or so I thought) with the story of the woman who had hurdled every barrier to reach the pinnacle of the legal profession. She was an icon. That said, I had never consciously considered tackling her biography. The idea came to me one morning as I was getting ready to go to work, from God's lips to my ear, as the saying goes. It seemed like such a good idea that I pursued it, and discovered that despite countless newspaper and magazine articles, there was no comprehensive study of her life or her place in the history of the state, legal history, or women's history.

It was a project begging to be done, and as a female, native North Carolinian, former history major, and attorney, I felt I had the background to take it on.

Q: Many associate Judge Sharp's name with a series of shocking family murders. Can you remind us about that?

A: Chief Justice Sharp retired in 1979. Several years later, in 1984 and 1985, a string of murders and suicides cost the lives of nine members of her extended family. Gripped by spiraling madness, her niece and nephew, Susie Newsom Lynch and Fritz Klenner (children of Susie Sharp's sisters Florence Newsom and Annie Hill Klenner), murdered Susie Lynch's ex-husband's mother and sister; Susie Lynch's parents and her paternal grandmother; and Susie Lynch's two little boys, before committing suicide by detonating a bomb in the SUV in which they were fleeing numerous law enforcement vehicles. Judge Sharp never got over this incomprehensible tragedy.

Q: Does Without Precedent tell the story that you intended to tell when you began your research?

A: It turned out to be even more remarkable than I had anticipated. I was interested in discovering how Susie Sharp carved out such an unprecedented career for a woman. I wanted to know the sources of her aspirations and the mechanisms by which she achieved positions held by very few men, let alone other women. The question that motivated me was, How did this happen? I discovered the answers to this question, but what I also discovered was a woman far more complicated and interesting than I had expected to find. Born in 1907, she was rooted in the 19th century, and she retained many deeply conservative ideas, including ideas about women, even as she vaulted over the limits set before her, often setting a modern example still useful today. Her public image as the quintessential spinster turned out to be highly sophisticated camouflage for a rich, unsuspected romantic life. In short, expecting to find a woman whose unrelenting focus on her career had perhaps rendered her somewhat one-dimensional, I found instead a woman worthy of Shakespeare in her many contradictions, conflicting desires, and paradoxical positions.

Q: You say that Sharp was in some ways deeply conservative, even though she was seen as a modern trail-blazer. What do you mean?

A: For one thing, she actually had a very traditional view of women's roles. She was proudly feminine, and relished the interplay between men and women. She liked feeling protected (even though she took the precaution of carrying a handgun in her pocketbook). This traditional view, however, vanished in the workplace, where she insisted, "Work has no sex." In another area, that of race, she was like many of her era mired in attitudes now no longer considered acceptable. Her feelings did not change on this issue, but her refusal to let them corrupt her profound belief in the rule of law stands as a monument in her life.

Q: Did you ever have a chance to meet or interview Susie Sharp?

A: Sadly, by the time I began work on this biography, her mind had failed, and I was unable to interview her.

Q: What kind of access did you have to Sharp's personal and professional files?

A: Susie Sharp's family gave me unlimited access to all of her professional files and personal papers, including the contents of her apartment after she died. This was a mountain of material, because she seemingly never threw away a piece of paper. I was able to examine everything from her correspondence as Chief Justice to notes that she had passed in class as a schoolgirl. I had virtually all the letters she ever received, in addition to carbon copies of those she wrote as an early devotee of the typewriter. I had family photograph albums dating from the late 19th century, as well as Susie Sharp's scrapbooks that she meticulously maintained all her life. And I had her journals covering more than 40 years.

Q: What kinds of challenges did you confront in mining these materials?

A: Other than the sheer volume, the main challenge was the fact that Susie Sharp's journals and some other items were written primarily in shorthand. Having never learned shorthand, I despaired. In the end, I realized that if I wanted to access the treasure trove the journals contained, I would simply have to teach myself. This I did. It then took me two years to translate and transcribe the journals.

Q: What was Sharp's upbringing like, and why did she pursue a career in law?

A: Susie Sharp's father was of yeoman stock, while her mother was descended from impoverished Southern aristocrats. Jim Sharp finally hit upon the law as a way of supporting his large family, and Susie grew up listening to his tales of the courtroom. By the time she graduated from high school, where she excelled as a member of the debate team, she had decided—despite the paucity of female role models—to become a lawyer. After two years at what was then called the North Carolina College for Women in Greensboro, North Carolina, she entered the University of North Carolina School of Law in Chapel Hill, the only girl in a class of 60 boys.

She graduated at the top of her class in 1929. As a woman, however, she would have been without a job, let alone a career, in the law, had her attorney father not brought her into his practice, thereafter known as Sharp & Sharp. It was politics, in which she and her father were deeply steeped, that brought her to the attention of Governor Kerr Scott, who in 1949 appointed her to be the first woman on the superior court.

Q: You mention that it's possible you know Susie Sharp better than any single person ever did. What do you mean?

A: I say this because I had the benefit of seeing her from every angle. Her professional colleagues and her public knew one version of Susie Sharp, her many friends and her family members knew another. None of these people knew that for her entire adult life she juggled as many as three romantic relationships at a time, relationships that lasted in each case for decades. With access to her journals and private correspondence, I was able to see how she functioned, giving her full attention to each aspect of her life while keeping them entirely separate.

Although she was deeply engaged in both political relationships and family matters, she was in many ways a lonely person, isolated as a woman because her life did not fit the normal female "narrative." She had girlfriends, married and single, but few if any of her professional status and achievement. She had virtually no reinforcement from other women except from those who admired her but were not her equals, no other women she could talk shop with, let alone discuss the anomaly of her professional prominence and the problems it posed. She did find such intimacy with her lovers, but in choosing married men—no doubt (whether consciously or unconsciously) partly as a means of preserving her profession—she was denied the companionship of marriage.

Q: What kinds of contributions did Sharp make to the state of North Carolina and to the legal profession?

A: As a trial court judge, Susie Sharp offered a sterling example of how a court should be run—knowledgeably, fairly, and efficiently—earning the respect of lawyers and litigants alike. She was a tireless crusader in her courtroom remarks and public speeches for the rule of law as the foundation of democracy, and for active, informed citizenship.

On the North Carolina Supreme Court, she was known as a legal scholar whose opinions were models of lucidity, and who undertook on occasion to bring about needed changes in the law. For example, she wrote the opinion in which the court overturned precedent to allow a patient injured by negligence to sue a charitable hospital. Her scholarly concurrence in another case gave a substantial impetus to the enactment of the state's Products Liability Act. Her opinion in a workmen's compensation case opened the door to a spate of brown lung cases, and prepared the way for lawsuits for a broader range of occupational injuries, such as those caused by repetitive motion. This had a major impact on important industries in the state such as textiles and poultry processing. Her dissent in a divorce case so powerfully revealed the inequity of divorce settlements that it led to passage of North Carolina's Equitable Distribution Act in the very next legislative session.

As chief justice, she did much to modernize the administration of the courts, lobbied for salaries to attract the best judges and court personnel, advocated for improvements in prison conditions, and held the judiciary to a high standard. As a woman, of course, through her example she expanded opportunities for women in the legal profession and public life.

Q: Was Sharp ever considered a candidate for the U.S. Supreme Court?

A: Susie Sharp was a perennial candidate for the U.S. Supreme Court. Governor Terry Sanford, who was in a position to harvest considerable political gratitude from President John F. Kennedy following the 1960 election, believed he could have secured her nomination, but she rejected his proposal. Later, she changed her mind and was willing to consider the possibility, but after Kennedy's assassination circumstances never again offered such a good opportunity. Surprisingly, it was President Nixon who appears to have considered her most seriously, despite her long record as an ardent Democrat.

Q: What was Sharp's position in the Equal Rights Amendment controversy?

A: Ironically, Susie Sharp was an obdurate opponent of the ERA. The battle for ratification in North Carolina raged from 1970 to 1982, while she was an associate justice and chief justice on the North Carolina Supreme Court. Despite her assurances to pro-ERA leaders that she would stay out of the fight, and despite her position on the court, she exerted every effort she could to defeat the amendment. She based her opposition largely on the arguable idea that women were already protected under the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and believed that the ERA would cause women to lose existing protections they had under the law. At the time, it was not at all clear what effect the ERA might have, and there were a number of well-respected legal scholars who voiced opposition. On the other side, there were strong arguments in favor of the ERA, and Susie Sharp's position was most unwelcome among women's advocates. North Carolina was considered a critical state whose approval could break the logjam and create momentum toward ratification. Justice Sharp was undeniably influential in the ERA's defeat in North Carolina, and to that extent, can be said to bear some credit or blame for its ultimate failure in the nation.

Q: Why do you think Sharp never married?

A: Along with her early decision to become a lawyer, Susie Sharp made up her mind that she would never marry. She had been plump and rather plain as a teenager, and perhaps felt somewhat defensive. As the eldest of seven children, relied on as a permanent baby-sitter, she had no illusions about the joys of motherhood. Until the end of her life, she believed she had to choose between her career and a family, an attitude that caused her some trouble with women's advocates. She also expressed a fear of the vulnerability love entailed, an aversion to giving up control over her feelings or her life. In law school, to her amazement, she fell deeply in love with a fellow student and discovered that she would give up everything to marry him. The relationship foundered, however, and she set out on her career course, meanwhile beginning long affairs with a former law professor and with an attorney, later judge, who would be one of her most important political mentors. Once she went on the superior court bench, she spent every week holding court all over the state, and liked to say that if she were married, her husband would "take up with a blonde" in frustration at her schedule.

Two decades after law school, she and her first love finally became lovers, and their relationship endured until the end of their lives. The only romance the public knew about, however, was her well-publicized "special friendship" with her colleague on the North Carolina Supreme Court, Chief Justice William H. Bobbitt. It was widely thought they would marry once they were both retired from the court but this never came to pass, although they remained devoted to one another.

Q: How do you think Sharp would view the place women occupy in the legal profession today?

A: She would be profoundly gratified that women attorneys and judges are considered professionals for whom the question of gender is irrelevant. She would not be surprised, however, that many women still struggle to reconcile the demands of career and family.